(P.S. 2022.12.2)

HIA 「国際俳句交流協会」の名称が「国際俳句協会」に変更されました。

(2019.1.13の記事)

芭蕉の高弟である服部嵐雪の辞世句とされる下記俳句のドイツ語訳について不審に思ったドイツの「俳句メル友」から、新年早々に、この俳句の解釈について問い合わせのメールを受信しました。

・一葉散る咄ひとはちる風の上

この俳句のドイツ語訳は次のとおり英訳してありました。

A single leaf falling

sheer lunacy!

A single leaf drifting away with the wind

そして、句友の英訳は次のとおりドイツ人らしい合理的な翻訳です。

Loosen from the tree

the helpless leaf

is drifting away on snowflakes

「sheer lunacy」は「愚行」とか「まったく馬鹿げたこと」と言うような意味です。(研究社大英和辞典)

「咄」は「叱る声」や「事の意外さに驚き怪しむ声」です。(広辞苑参照)

そこで、「咄」は座禅に使われる「喝」と同じような一種の擬音であること、この俳句の「葉」は「人間」の比喩と捉えるのが良いと思う旨説明し、次のとおり筆者独自の大胆な意訳を連絡したところ、「amazing!」と感嘆した旨の返信が来ました。

man dies as a leaf falls_

Basho has passed away,

now, me too.

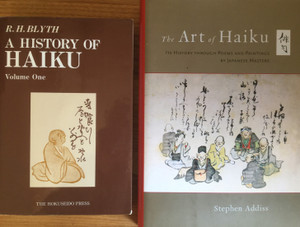

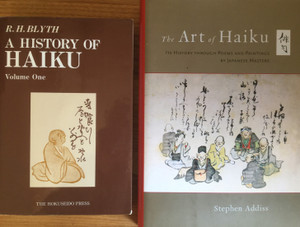

因みに、R. H. Blyth 氏は A History of Haiku (Volume One) において、「この辞世句は美しいが、何か nerveless である」と付記して、次のように文字どおり英訳しています。

A leaf falls,

Totsu! Another leaf falls,

Carried by the wind.

「nerveless」は研究社大英和辞典によると「弱弱しい」とか「冷静な」という意味ですが、Blyth はどちらの意味を指しているのでしょうか?

Stephen Addiss 氏は The Art of Haiku において、「『咄』は禅の叫び声である」と付記して、次のとおり英訳しています。

a leaf falls

Totsu! a leaf falls_

riding the wind

上記2氏の英訳は「風に運ばれる」とか「風に乗る」と英訳していますが、嵐雪は「風の上」と表現して「昇天」を暗示したのではないでしょうか?

さらに、「咄」と擬音で注意を喚起して、「ひとはちる」と「ひらがな」を用いて「人は散る」と読ませることを意図していたのではないでしょうか?

穿ちすぎでしょうが、高浜虚子は嵐雪の辞世句が潜在意識にあって「春の山屍を埋めて空しかり」に同じように「ひらがな」を用いる手法を使ったのかもしれません。

英語は論理的な言葉ですから日本語ほど連想を伴いません。比喩的な俳句は文字通りの英訳と意図された比喩の意訳を併用すると日本語の原句にある暗喩のニュアンスが理解されやすいと思っています。

国際俳句交流協会HP掲載の「高浜虚子の俳句をバイリンガルで楽しもう!」をご覧下さい。

俳句の翻訳に興味があれば、「俳聖の偉蹟を尋ね秋の伊賀(俳句と写真)」や「俳句の国際化 <言葉の壁を破るチャレンジ>」をご覧下さい。

(青色の文字をタップするとリンクされた記事をご覧になれます。)

青色文字をタップすると、最新の「俳句(和文)」や「英語俳句」の記事をご覧頂けます。

トップ欄か、この「俳句HAIKU」をタップすると、最新の全ての記事が掲示されます。